Crossing the Delaware in Durham Boats Part 1

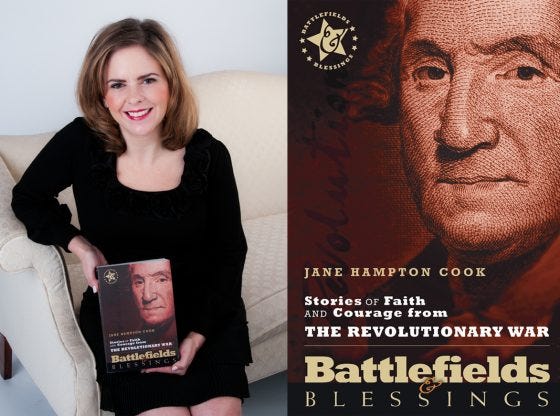

Adapted from Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War

Kevin McCarthy, the new Speaker of the House of Representatives, mentioned the famous story of George Washington crossing the Delaware River in Durham boats in his acceptance speech on Jan. 7, 2023. Here is the story of George Washington crossing the Delaware River with his army based on original source material from George Washington and Henry Knox. Adapted from Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War by Jane Hampton Cook.

“The Jerseys; it was really in the hands of the enemy before my arrival,” Gen. Charles Lee later said about his march through New Jersey and his capture in December 1776. And although folly was his downfall, Lee was right on this point. After the fall of New York, the state of New Jersey fell into the chaos of a civil war. Locals fought each other with vengeance.

“As Washington flees across New Jersey and people are unwilling to help them, he fully realizes that this revolution might be over. He’s the commander-in-chief of an army that has shrunk drastically. He’s on the run with the enemy on his heels,” historian Bruce Chadwick explained in an interview for The History Channel Presents: The American Revolution, 2006.

The state of New Jersey brought a black cloud of discouragement over Washington.

“This being perfectly well known [New Jersey loyalty] to the enemy, they threw over a large body of troops, which pushed us from place to place till we were obliged to cross the Delaware with less than 3,000 men fit for duty, owing to the dissolution of our force by short enlistments; the enemy’s numbers, from the best accounts exceeding ten and by some 12,000 men,” General Washington wrote from Trenton in a letter to his brother on December 18, 1776.

Rain fell from Washington’s dark cloud as he considered the approaching deadline. Many of his men’s enlistment terms would expire at the end of the year, just days away.

“We are in a very disaffected part of the Province; and, between you and me, I think our affairs are in a very bad situation,” General Washington told his brother. He had no doubt General Howe wanted to take Philadelphia. But he also knew his men were too weak to stop Howe. “In a word, my dear Sir, if every nerve is not strained to recruit the new army with all possible expedition, I think the game is pretty near up.”

Washington sprinkled his letter with further evidence that the contest seemed over for the Americans. The colonies were losing their resolve.

Congress was relying too much on inexperienced militia. “You can form no idea of the perplexity of my situation. No man, I believe, ever had a greater choice of difficulties, and less means to extricate himself from them.”

The commander-in-chief may have been discouraged, but he was also a sunny optimist.

“However, under a full persuasion of the justice of our cause, I cannot entertain an Idea, that it will finally sink, tho’ it may remain for some time under a cloud,” George Washington concluded.

Righteousness of the cause gave him hope tor a rainbow.

PRAYER

Thank you for your promise of the rainbow, the covenant of encouragement you have made with us.

The Crossing

The strategic fork in the road George Washington faced at the end of December 1776 was more than the intersection of defense and offense. The choice he made could affect the “fate of unborn millions,” as he had reminded his troops before the battles of New York. God had preserved the army with a fog, a bridge, and a general’s blunder.

And so it is no wonder that Washington turned to the unexpected for his last attempt to regain the confidence of Congress and convince his men to stay in the army past their December 31st enlistment expiration. In a tactical about-face, Washington switched his troops’ direction from defense to offense.

“The evening of the twenty-fifth I ordered the troops intended for this service to parade back to McKonkey’s Ferry, that they might begin to pass [over the Delaware River] as soon as it grew dark, imagining we should be able to throw them all over, with the necessary artillery, by twelve o’clock, and that we might easily arrive at Trenton by five in the morning, the distance being about nine miles,” recorded Washington about his decision to send his men in flat-bottomed boats from Durham, Pennsylvania, over the Delaware River to launch a surprise attack against the British outpost guarded by the Hessians, who were German mercenaries.

The commander-in-chief knew the Germans held hearty celebrations. Feast days such as Christmas were no exception. A night of wine might decrease the resistance of Colonel Rahl and his nearly two thousand soldiers. The strategy of surprise had served Washington well before. After all, it was the sudden appearance of Fort Ticonderoga’s cannons on Dorchester Heights that drove the British from Boston in March 1776.

There were, however, numerous icy kinks, clinks, and chunks obstructing his December surprise. The river was more solid than his timetable.

“But the quantity of ice, made that night, impeded the passage of the boats so much, that it was three o’clock before the artillery could all be got over; and near four before the troops took up their line of march,” Washington wrote in anguish.

The crossing was to begin at nightfall, with hopes of forging the Delaware River before midnight. Washington wanted to have plenty of time to march the nine miles by land under the cover of darkness. The four-hour delay put the army in great danger of someone seeing them in the sunrise and alerting Rahl. “This made me despair of surprising the town, as I well knew we could not reach it before the day was fairly broke,” he wrote of their tardiness.

As much as he hoped to surprise the Hessians, the delay forced George Washington to another crossroad. Should he abandon his plans and retreat to safety by re-crossing the river? Or should he press on to Trenton with the knowledge that a loyalist might alert the Germans? The decision could prove as treacherous as crossing the Delaware.

PRAYER

God, send your angels to surround me when life takes me through treacherous waters and consuming fire.

Raging River

The storm continued to rage while George Washington contemplated whether to re-cross the Delaware River or attack Trenton on the morning of December 26, 1776. Perhaps no one felt the chill of the icy river and the scourge of the night crossing more than the man in charge of the artillery. The responsibility of ferrying the men and ammunition across the river fell to the meticulous mind and attentive arms of Henry Knox.

“A hardy design was formed of attacking the town by storm,” Knox wrote, describing the plan in a letter to his wife, Lucy. Knox explained his perspective behind Washington’s decision to cross in the first place.

The enemy “had obliged us to retire on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware, by which means we were obliged to evacuate or give up nearly all the Jerseys.”

Not long after the Continentals formed their camp, they discovered “the preservation of Philadelphia was a matter exceedingly precarious,—the force of the enemy three or four times as large as ours.”

Knox was often the first to analyze the strength of the enemy, based on their arms. He noted the British army had scattered their troops at “distant places in New Jersey,” but Trenton’s “cantonments” were the largest. “Trenton is an open town, situated nearly on the banks of the Delaware, accessible on all sides. Our army was scattered along the river for nearly 25 miles. Our intelligence agreed that the force of the enemy in Trenton was from two to three thousand, with about six field cannon, and that they were pretty secure in their situation,” he wrote of the Hessian regiment based there.

Knox then used matter-of-fact terms to tell Lucy about that cold and challenging night of 1776. “Accordingly a part of the army, consisting of about 2,500 or 3,000 passed the river on Christmas night, with almost infinite difficulty, with 18 field-pieces. The floating ice in the river made the labor almost incredible,” he wrote, not mentioning the challenge of finding enough Durham boats to carry the men and ammunition across and conducting the affair in silence. Two men died of frostbite after crossing the river. The army also left bloody footprints behind in the ice and snow. “The night was cold and stormy; it hailed with great violence; the troops marched with the most profound silence and good order,” he reported.

But the sleet did not subside after they arrived on the New Jersey side. The approach of daylight did not dissipate the hail or the storm.

“The storm continued with great violence, but was in our backs, and consequently in the faces of our enemy,” he wrote. Knox then made an important conclusion after the crossing. Diligence had overcome the raging river.

“However, perseverance accomplished what at first seemed impossible,” Henry Knox concluded of the Delaware crossing.

PRAYER

Father, thank you for the gift of faith that secures raging rivers and allows me to cross onto unknown shores.

I'll try to hunt it down for you

It was read during a Christmas celebration I listened to on a podcast.

It was really something....

Would you write about the miracle of the shad fish that saved his men from starvation?