How Many People Could Vote When America Was Founded?

Excerpt from Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists and Women's Battle for the Vote

Election integrity is in the news today as I prepare this post. The Arizona Supreme Court ordered a lower court to hear evidence on signature verification in the Kari Lake for Governor case. This is good news for election integrity, which is the new civil right of our time. Now that all U.S. citizens over the age of 18 have the right to vote, ensuring that the entire voting system has integrity is one of the most important issues of our time regardless of political party.

Likewise, as I write this post, March is Women’s History month, and March 31 is the 247th anniversary of Abigail Adams’s call to remember the ladies.

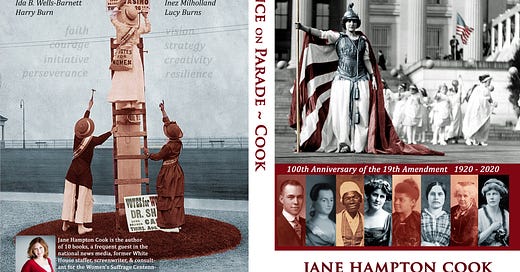

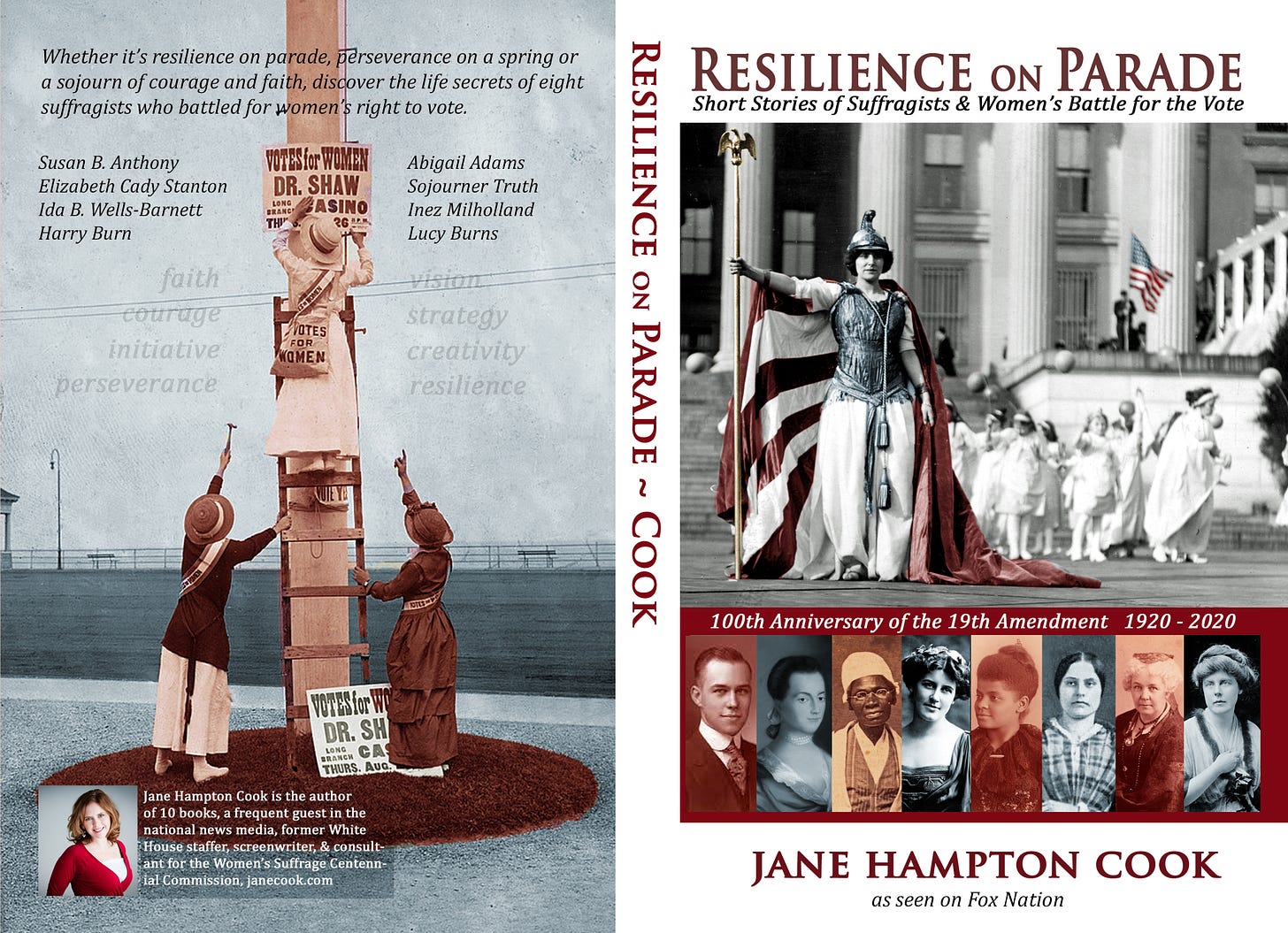

A few years ago, I researched the start of voting in America for a book. Resilience on Parade celebrated women’s suffrage in 2020, the anniversary of women winning the right to vote throughout the United States through ratification of the 19th Amendment. After a government agency pushed me to call Susan B. Anthony a racist in 2019, which I refused to do because she was an abolitionist and I lost the writing job as a result, I saw a need for an originalist interpretation on women’s battle for the vote.

Below is an excerpt from Resilience on Parade that is based on original sources. I could use a few more Amazon reviews of this book. If you are interested in receiving a free ebook and reviewing it on Amazon, send an email to info@janecook.com subject: send Resilience on Parade and I can email you what is known as a review copy. You are welcome to buy a copy and give it as a Mother’s Day gift.

Enjoy!

In the lead-up to the Declaration of Independence, Abigail Adams often had taken initiative with John on his behalf and at his request. “I need not tell you, Sir, that the distressed state of this province calls for every excursion of every member of society,” Abigail had written to a London bookseller at the request of her husband shortly after the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. John had wanted her to impress upon this Londoner their situation in the hopes that he would support their cause.

“The spirit that prevails among men of all degrees, all ages and sexes is the spirit of liberty. For this they are determined to risk all their property and their lives nor shrink unnerved before a tyrant’s face,” she wrote in May 1775.

If the war was affecting every member of society, and each was fighting for liberty, then shouldn’t all adults have a say in who represented them? That was Abigail’s natural conclusion.

* * * * *

In the months leading to the Declaration of Independence, Abigail expressed this view to John in a personal way. Just as she’d passed along the frank opinions of their neighbors and their concerns about the lack of silver and the unfairness of the liquor tax, so she had also shared her views about a matter that meant a great deal to her. Freely giving her opinion on what should guide John and the Congress as they created a new constitution, she also suggested they keep a specific word in mind.

“And by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors,” she wrote John on March 31, 1776.

Abigail didn’t hold back.

“Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember all men would be tyrants if they could,” she continued, underscoring her point with teasing and hyperbole.

“If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation.”

Though John had frequently addressed her as “my friend” and treated her as an intellectual equal, Abigail knew he was the exception. She didn’t hold the same opinion of other men.

“That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend.”

Abigail wanted her husband to protect women from those who didn’t respect women the way that he did.

“Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your sex,” she continued, using the feudal term vassal to underscore her point that all men were not uniformly lords over all women.

“Regard us then as beings placed by Providence under your protection and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness,” she concluded.

Abigail could trace her interpretation to scripture and John Locke, who had pointed out that “whatever God gave by the words of this grant, Genesis 1:28, it was not to Adam in particular, exclusive of all other men: whatever dominion he had thereby, it was not a private dominion, but a dominion in common with the rest of mankind.”

Locke saw mankind as humanity, both male and female. As Locke noted, God didn’t give dominion to Adam alone: “For it was spoken in the plural number, God blessed them, and said unto them, have dominion. God says unto Adam and Eve, have dominion.”

Locke asked this question about Eve: “Must not she thereby be lady, as well as he lord of the world?” He suggested the dominion of Adam and Eve was mutual. “If it be said, that Eve was subjected to Adam, it seems she was not so subjected to him, as to hinder her dominion over the creatures, or property in them: for shall we say that God ever made a joint grant to two, and one only was to have the benefit of it?”

No, Locke believed. Both male and female were to have dominion. Both had natural rights, which came from God. Abigail obviously agreed. But did her Adam concur? How did he respond?

* * * * *

On the surface, John didn’t take seriously Abigail’s suggestion to remember the ladies. “As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our struggle has loosened the bands of government everywhere,” he wrote her on April 14, 1776, noting that different groups had taken advantage of the lack of government.

“But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe more numerous and powerful than all the rest were grown discontented.—This is rather too coarse a compliment but you are so saucy, I won’t blot it out.”

He tried to soften the blow.

“Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory.”

Then Mr. Adams tried to turn the tables.

“We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair, and softly, and in practice you know we are the subjects. We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave heroes would fight.”

Though Adams didn’t appear to take his wife seriously, he in fact did think about it. A lot. In May 1776, he engaged in a debate over the question of who had the right to vote in the new government they wanted to build.

* * * * *

In May 1776, Adams read a letter from James Sullivan, a Massachusetts lawyer, who had sent his thoughts about a new code of government to their mutual friend Elbridge Gerry. Sullivan was excited, because leaders in Massachusetts were creating a new legislature. In the lead-up to the Revolutionary War, a British governor had abolished the Charter of Massachusetts Bay Colony and dissolved the legislature. Now it was time to build a new state government.

“A new assembly is at hand in which there will be the most full and equal representation that this colony ever saw. This assembly will undoubtedly suppose it to be their duty to provide for a future less unwieldly and more equal representation than themselves,” Sullivan stated, agreeing with Common Sense that government should be founded on the people’s authority.

“Laws and government are founded on the consent of the people, and that consent should by each member of society be given in proportion to his right,” he wrote, believing it was time to think about a new way of giving people a voice. “In order to do it must we not lay aside our old patched and unmeaning form of government?” The way to fix the old government was to ensure that the new one was based on the people’s consent.

“Every member of society has a right to give his consent to the laws of the community or he owes no obedience to them,” he wrote, noting that this was a true republican principle.

But Sullivan saw a huge flaw in the old system.

“And yet a very great number of the people of this colony have at all times been bound by laws to which they never were in a capacity to consent not having estate worth 40/ per annum &c.”

What was he talking about? In order to vote in Massachusetts, one had to own land worth forty shillings a year. The result was that only 16 percent of the population was eligible to vote. Of those eligible, only 3.5 percent of the population had voted in the decade before 1774, when the king abolished the Massachusetts government and implemented martial law under a British general. Sullivan saw the contradiction. If only landowners could vote, then more than 80 percent of the people had no voice in choosing their representatives. The resulting system favored the upper class.

Rarely did women own land, much less vote. The rare exception was Lydia Taft of Uxbridge, Massachusetts. When her husband died, she was asked to vote in a town meeting in 1756 during the French and Indian War. Her vote was necessary, because the town needed money from her land to fund the militia. They sought her consent, and she gave it to them.

Lydia Taft lived more than 110 miles from Sullivan, who was born in Berwick, Massachusetts, which is now part of Maine. Nonetheless they shared a common impulse to expand the consent of the governed. Sullivan, who’d recently been appointed to the highest court in Massachusetts in March 1776, was weighing this important principle.

“But yet by fiction of law every man is supposed to consent. Why a man is supposed to consent to the acts of a society of which in this respect he is absolutely an excommunicate, none but a lawyer well dabbled in the feudal system can tell,” Sullivan criticized. The current system was blind to this injustice.

Where did this voting structure come from? It originated in the feudal system, in the medieval era of knights and lords. A landlord owned property. His wife, children, servants, and renters, called vassals, all depended on the landlord. The relationship between landlord and vassals was more than just a financial obligation to pay rent once a month. The renter also owed his landlord his service.

Imagine in our modern culture if you rented a house or an apartment. You would pay your landlord a monthly amount in rent and sign an agreement on maintenance for the property. That’s it. You wouldn’t depend on your landlord for food or a job. If the feudal system were in place, your landlord would also be your boss, giving you instructions and overseeing your work. Your landlord would be your captain in the military, who could order you to the battlefield. Imagine being required to vote the same way your landlord voted. In this structure, the landlord is the only one free and clear of dependency.

“The scars and blotches of the feudal system, the footsteps of vassalage, and the paths to lawless domination compose so great a part of it, that no friend to his country can wish to see it ever put in exercise again,” Sullivan wrote, wanting to unshackle his fellow patriots.

Though the medieval era had died out in the 1400s, and many of the obligations between a renter and landlord had disappeared by the 1770s, owning land was still power. In fact, John Locke had used the word “property” 181 times in his Two Treatises of Government.

In the 1700s, men and women who did not own land depended on someone who did. Children still depended on women, and women could not go fight because children needed them. Artisans depended on patrons, who were landowners. Renters still depended on landowners for their food and homes. Working-class men, such as blacksmiths, often rented land. All depended on the landlord. They could not vote of their own free will because they had a bias, a debt to a landowner.

The result was that only people who had a free will and were not dependent could vote. Though the words “vassal” and “feudal” weren’t in vogue in 1776, the landlord, also called a freeholder, was still the only one in society who was free and clear of dependency. Hence, he could vote freely without obligations to anyone else. In this way, he came to the voting booth independent and unbiased, theoretically not beholden to anyone else’s interests.

Excluded from voting were laborers, tenant farmers, unskilled workers, and indentured servants, as well as slaves, women, and children. The result was discrimination and distinctions by class. Some men, in addition to women and minorities, were discriminated against.

Sullivan saw a problem with only landowners voting. He understood the contradiction inherent in declaring that rights come from God and creating a government based on the people when not all people had a say in their consent. The idea that all were equally free and independent contradicted the fact that voting was only available to those who owned land and could vote free and clear of dependency on others. If everyone had to obey the law, shouldn’t they have a say in who makes the law?

“For where there is a personal or corporal punishment provided, all subjects are equally concerned—the persons of the beggar, and the prince being equally dear to themselves respectively,” he wrote. “Thus, Sir, the poor and rich are alike interested in that important part of government called legislation.”

Though rich and poor alike were under the same criminal laws, they differed in the amount of taxes they owed. “But in the supporting the executive parts of civil government by grants and supplies of money, men are interested in proportion to their estates.”

* * * * *

How did John Adams respond? He answered Sullivan in a way that showed he’d been thinking about his wife’s call to remember the ladies.

“It is certain in theory, that the only moral foundation of government is the consent of the people. But to what an extent shall we carry this principle? Shall we say, that every individual of the community, old and young, male and female, as well as rich and poor, must consent, expressly to every act of legislation? No, you will say. This is impossible,” John Adams wrote to Sullivan on May 26, 1776.

John, who didn’t own slaves, thought about the 84 percent of society that couldn’t vote.

“But let us first suppose that the whole community of every age, rank, sex, and condition, has a right to vote. This community is assembled—a motion is made and carried by a majority of one voice. The minority will not agree to this. Whence arises the right of the majority to govern, and the obligation of the minority to obey? From necessity, you will say, because there can be no other rule.”

He gave his views on women voting.

“But why exclude women? You will say, because their delicacy renders them unfit for practice and experience, in the great business of life, and the hardy enterprises of war, as well as the arduous cares of state. Besides, their attention is so much engaged with the necessary nurture of their children, that nature has made them fittest for domestic cares.”

He explained that children weren’t old enough to make decisions and vote before addressing men who didn’t own land.

“Is it not equally true, that men in general in every society, who are wholly destitute of property, are also too little acquainted with public affairs to form a right judgment, and too dependent upon other men to have a will of their own?” he asked. “If this is a fact, if you give to every man, who has no property, a vote, will you not make a fine encouraging provision for corruption by your fundamental law?”

He saw non-landowners as a biased special interest loyal to those they depended on.

“Such is the frailty of the human heart, that very few men, who have no property, have any judgment of their own. They talk and vote as they are directed by some man of property, who has attached their minds to his interest.”

At the root of all of this was fear. Adams feared that the rights of property owners might be overruled by a majority of non–property owners. He understood the problem that non-landowners had to follow the laws.

“Your idea, that those laws, which affect the lives and personal liberty of all, or which inflict corporal punishment, affect those, who are not qualified to vote, as well as those who are, is just. But, so they do women, as well as men, children as well as adults.”

“The same reasoning, which will induce you to admit all men, who have no property, to vote, with those who have, for those laws, which affect the person will prove that you ought to admit women and children,” he pointed out, acknowledging the logic of opening up the vote to non-landowners.

He viewed men without property in the same way that he viewed women and children.

“For generally speaking, women and children, have as good judgment, and as independent minds as those men who are wholly destitute of property: these last being to all intents and purposes as much dependent upon others, who will please to feed, clothe, and employ them, as women are upon their husbands, or children on their parents.”

He feared that if Massachusetts gave all men, regardless of class or lack of land ownership, the right to vote, “there will be no end of it. New claims will arise.

Women will demand a vote. Lads from 12 to 21 will think their rights not enough attended to, and every man, who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks, to one common level.

“If the multitude is possessed of the balance of real estate, the multitude will have the balance of power, and in that case the multitude will take care of the liberty, virtue, and interest of the multitude in all acts of government,” he wrote, believing that it would be wise not to change voting qualifications.

The debate between Adams and Sullivan over who should vote, along with Abigail’s cry to remember the ladies, continued in the debate held by the framers of the U.S. Constitution. Meeting in Philadelphia, the members of the Constitutional Convention debated the question of allowing only landowners to vote. Unable to reconcile the issue, they punted.

The framers of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 left the details of who could vote to the states. Article I, section 4 of the Constitution says:

“The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations.” The Constitution let the states determine who was eligible to vote. Most states kept the status quo by allowing only landowners to vote. In their minds, this was less about discrimination than about unbiased voting.

Despite his opposition to non-landowners voting, John Adams understood the contradiction. He knew that men who owned land had access to education because of their wealth. He understood that owning land carried prestige and opportunity. He closed his debate with Sullivan with a recommendation on solving this disparity.

“Nay I believe we may advance one step farther and affirm that the balance of power in a society, accompanies the balance of property in land,” he wrote.

His solution was to make more people free of obligations to others by enabling them to become landowners.

“The only possible way then of preserving the balance of power on the side of equal liberty and public virtue, is to make the acquisition of land easy to every member of society: to make a division of the land into small quantities, so that the multitude may be possessed of landed estates.”

* * * * *

Abigail Adams couldn’t convince her husband to add the word “women” or “ladies” to either the Declaration of Independence or the Massachusetts Constitution. Though the masses were ready to initiate independence, they weren’t ready to initiate equality when it came to voting. Taking initiative succeeds best when there is enough support for the idea. Independence from England could set sail because it was driven by the strong winds of favorability in society.

While Abigail’s ship of equality faced stale winds, she certainly wasn’t alone. Sullivan saw the problem that the Declaration of Independence created by calling for a government based on the consent of the governed while only allowing a small percent of the population, the landowners, the right to vote. With only 3.5 percent of the population actually exercising the vote in the years before the Revolution, the battle to remember the ladies had much to overcome.

Gender is part of our modern definition of diversity. Today we define diversity by gender or sex, race, ethnicity, and class and tend to view the founding era as lacking diversity. But that’s not how John Adams saw it.

John and Abigail opposed slavery. He’d supported a passage that Thomas Jefferson wrote for the Declaration of Independence opposing slavery:

“The Christian king of Great Britain [is] determined to keep open a market where men should be bought and sold, . . . suppressing every legislative attempt [by the American colonists] to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce.” Twenty-five percent of Jefferson’s original draft was cut, including this passage.

Adams believed there was much diversity in the founding era. In fact, to him, the diversity of the United States made it a miracle that it had come together in the first place. Diversity to Adams was found in religion, primarily the different sects or denominations of Christianity, as well as in Judaism.

Defining diversity by religion is a hard concept to grasp in the world today, where all denominations of Protestant and all Catholics are lumped into the category of Christian. But understanding Adams’s view of diversity and the challenges it posed puts independence and the lack of universal voting practices into better context.

“But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The revolution was affected before the war commenced,” John Adams asked a newspaper editor in 1818.

“The revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people. A change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations,” he continued, before concluding, “This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments and affection of the people, was the real American Revolution.”

He saw a difference between Maryland, which was founded by Catholics, and Pennsylvania, which welcomed all religions, from Jews to Quakers. Religion had influenced the different charters of the colonies.

“The colonies had grown up under constitutions of government, so different, there was so great a variety of religions, they were composed of so many different nations, their customs, manners and habits had so little resemblance, and . . . their knowledge of each other so imperfect, that to unite them in the same principles in theory and the same system of action was certainly a very difficult enterprise.”

The diversity of the colonies wasn’t as simple as Christian versus non-Christian but was defined by different sects within Christianity and beliefs about Judeo-Christian theology and values. To John Adams, European Americans were very diverse. A French Catholic was different from an Irish Catholic, and an Irish Catholic was different from an Irish Protestant.

“By what means, this great and important alteration in the religious, moral, political and social character of the people of thirteen colonies, all distinct, unconnected and independent of each other, was begun, pursued and accomplished, it is surely interesting to humanity to investigate, and perpetuate to posterity.”

Adams wrote about the real revolution in February 1818. By this time, more men had gained or were gaining the right to vote without owning land. A few months later, in October, Abigail died at the age of 73. She had continued to remember the ladies throughout her life, showing her resilience and her steadfast faith in her beliefs.

On one occasion, in 1793, her sister Elizabeth said to her, “I wish you would be so kind as to lend me the Rights of Women—the first opportunity.” The Rights of Women was a book by British author Mary Wollstonecraft, who advocated women’s education.

Her daughter, Mary Shelley, later gained fame as the author of the novel Frankenstein. John had teased Abigail that she was a disciple of Wollstonecraft. And indeed, education for women would pave the path for ladies in the future, enabling them to fight for the right to own land and the right to vote.

* * * * *

The initiative of another Revolutionary War patriot would inspire his granddaughter in the years to come. Descended from the Scottish-Catholic line of Lord Livingston, Colonel James Livingston made a pivotal decision that forever changed American history. While on duty at West Point in 1780, Livingston “took the responsibility of firing into the Vulture, a suspicious looking British vessel that lay at anchor near the opposite bank of the Hudson River.”

The Vulture responded to Livingston’s shot by fleeing, leaving a British spy, British major John Andre, behind American lines.

“It was a fatal shot for Andre, the British spy, with whom [Benedict] Arnold was then consummating his treason.” Livingston had thwarted Andre’s escape ship. Andre had been plotting with General Benedict Arnold, who committed treason when he gave Andre the plans to West Point. With the Vulture gone, Andre had to walk back to the British lines.

Andre was captured and later executed, but Arnold escaped. Colonel Livingston’s granddaughter, Elizabeth, later explained:

“On General Washington’s return to West Point, he sent for my grandfather and reprimanded him for acting in so important a matter without orders, thereby making himself liable to court-martial.” Calming down, Washington “admitted that a most fortunate shot had been sent into the Vulture, for . . . the capture of this spy [Andre] has saved us.”

Through this event, Livingston passed down a legacy of taking initiative to his granddaughter Elizabeth. The risk Elizabeth later would take would change the tide in the battle to accomplish Abigail’s call to remember the ladies.