Mother's Day: How Motherhood has influenced my historical books

Motherhood is an important human tie that can help us better understand our nation's history.

This substack will be a bit more personal than my other substacks to date. When I think of Mother’s Day, I think of my three sons as well as my mother and grandmothers.

As someone who battled infertility and long desired to be a mom before I actually became one, Mother’s Day was really hard for me for several years until my husband and I welcomed our first child.

Mother’s Day, of course, was also always about my own mom. I had a terrific and close relationship with my mother, but I lost her to Parkinson’s three days after Mother's Day eight years ago.

In our last conversation, I called her for Mother’s Day. My mom couldn’t say much but smiled in recognition while I babbled on about baking her German apple kuchen recipe for international day at my sons' school. That recipe had a special memory for us because she had acquired it while my dad, who was a lieutenant in the US. Army at the time, was stationed in Germany, where I was born.

My strong relationship with my mother gave me a positive view of motherhood and influenced my writing. Over the years when writing about female historical figures, I have paid attention to how motherhood played a role in their personal stories and subsequently, our nation's history.

Had I had experienced a strained relationship with my mom, I don't know that I would have been drawn to the theme of motherhood in the lives of Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Louisa Adams, Dolley Madison and several of the suffragists.

Though most of the people in my book, Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War, are men, I made sure to include stories about Martha Washington and Abigail Adams. I discovered that Martha gave up being present at the birth of her grandchildren to stay with George Washington in winter camp during the American Revolution. Though we can't relate to traveling great distances on unpaved roads in a carriage, because of motherhood, we can recognize the sadness and disappointment she felt and the sacrifice she made for our nation. Missing these births pained her greatly, but she felt she needed to be with General Washington as he battled taking care of the material needs of his army and crafting a strategy to defeat the British military. Spending 50% of the war in camp with her husband during the non-fighting seasons, Martha became a mother figure to the army.

Likewise, motherhood played a role in Abigail Adams’s life during the American Revolution. Because her husband, John Adams, gave up his law practice to attend the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Abigail became the sole breadwinner while caring for their four children in Massachusetts.

Adams trusted Abigail’s judgment so much that he asked her to manage their farms. Abigail had to deal with wayward tenants, counterfeit money, and the possibility of the British army traipsing through her farmland and threatening her family. Little did she know at the time, but she was married to a future president of the United States while also raising a future president of the United States, John Quincy Adams.

John Quincy brings me to perhaps the most distressing story of motherhood that I have ever encountered in my historical research and book writing. While on a diplomatic mission for President Washington to London, John Quincy married Louisa Johnson, a British-born American in delicate health. Louisa spoke French fluently and likely spoke English with a French accent because she spent her childhood in France. As a result, some people did not consider her to be an American, despite her patriotic pronouncements.

When John Quincy was appointed as the first U.S. diplomat to Russia in 1809, Louisa was asked to accompany him. Because French was the language of diplomacy, her French language skills would help her to represent America as she communicated with the diplomats and the tsar of Russia at balls, ballets and other social events.

But her in-laws, John and Abigail Adams, insisted that she leave two of her three sons behind in Boston. She was only allowed to take her two-year old son, Charles, on their voyage. Louisa accurately perceived that she had no say in the matter. Because we can relate to motherhood, we can understand the trauma that Louisa experienced.

Yet, it is hard for us to understand why John and Abigail demanded that John Quincy and Louisa leave George, age 8, and John age 6, behind with them in Massachusetts. It is easy to judge them as being cold-hearted but, unlike today, traveling back then was very unsafe. Ships frequently sank. John and Abigail were fearful that if all three of John Quincy's children accompanied him to Russia, then their entire family line could end up at the bottom of the ocean.

Likewise, John Adams had served on diplomatic missions to France and England. He did not want his grandchildren corrupted by the different moral standards that were often found in diplomatic circles, especially in Russia, which was considered one of the most lavish courts in Europe. Only Napoleon's court in France exceeded the splendor of the Russian court at this time.

Louisa and John Quincy thought they would only be away from their children for a year. Multiple interruptions, including two wars, kept them in Russia for six years. Because we can relate to motherhood, at the end of the story we can understand Louisa's willingness to confront any danger, including coming face-to-face with Napoleon, to be reunited with her children in 1815.

Though I wrote about Louisa and John Quincy Adams equally in my book American Phoenix, Louisa's motivation as a mother gives us greater insight into the sacrifices she made for America.

John Quincy and Louisa’s Russian destination changed U.S. destiny because they forged a relationship with the tsar of Russia on behalf of the United States. This led to a peace treaty between England and America to end the War of 1812.

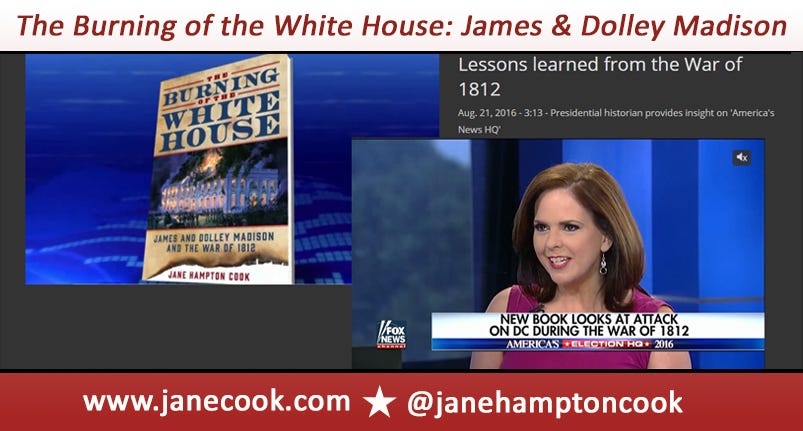

When I wrote about Dolley Madison in my book, The Burning of the White House, I discovered that mothering was also a part of her persona and personal history. She had lost an infant son and her first husband to the yellow fever and had one surviving son. Many people whispered that her marriage to James Madison was one of convenience because they never had a child together. But my historical research revealed that she had a miscarriage when Madison was Secretary of State. While silently grieving about never having a child with Madison, she had to endure accusations of having a loveless marriage from her husband's political enemies.

But Dolley's nurturing, maternal nature came out in the way she socialized. She frequently took in teenage girls at the White House, taught them manners and how to be a part of society.

Dolley's nurturing nature also played a role in her desire to do something that no other wife of a president had done before her—start a charity.

The burning of the White House by the British military in 1814 devastated her. Because a year later she started charity for girls who had lost a parent, the loss transformed her from a hostess into a humanitarian, earning her the name “first lady of the land” at her death. She is considered the first, first lady, in part because of her charity for orphans living in Washington DC. This organization still exists today as a non-profit.

Motherhood also helped me to relate to some of the suffragists who lobbied for women's right to vote for over a century. Starting with Abigail Adams, I highlighted several of them in my book Resilience on Parade.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a mother, as was Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells Barnett. Stanton’s sympathy for widowed mothers who could not own land in New York motivated her to seek legislation to change land ownership laws for women, and then later to lobby for women’s voting rights.

In the 1800s, Sojourner Truth helplessly watched her slave owner send her children away to other slave owners. This denied her the ability to raise all of her children.

After she became a free person, she wrote about her children and slave story in a published narrative that was used to call for abolishing slavery. Sojourner became a public speaker, an abolitionist and an advocate for women's voting rights in the 1850s.

Motherhood also played a significant role in the final vote that ratified the 19th Amendment in 1920, which allowed all women in all states to vote. Women who lobbied members of Congress and their state legislators often reminded them that their wives, daughters, sisters and mothers deserved the right to vote.

Motherhood influenced the final vote to ratify the 19th Amendment, which came down to one Tennessee legislator, Harry Burn. Because he was under tremendous pressure from his political mentor to oppose the amendment, Burn was originally a “no” vote. But when he received a letter from his mother the morning of the final vote, he reflected on the fact that his mother ran their farm after his father died. She was just as engaged in commerce as the men who served as laborers on the farm. Yet, they had the right to vote, when she did not, even though she was the manager.

During the final vote in the Tennessee House, Burn changed his vote to “aye,” shocking the house chamber and sending the suffragists in the gallery into a joyous frenzy. Thanks to Harry Burn and his mother, Tennessee became the final state needed to ratify the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.

Today, motherhood is under attack. Some on the radical left are trying to replace the word mother with the ridiculous term of birthing person. Motherhood is far more than just giving birth. Canceling words is a Marxist tactic that erases and diminishes women and their importance as mothers.

This Mother's Day, let us be grateful for the mothers in our lives and the historical mothers who contributed to our nation's history. Let us celebrate motherhood and preserve its importance in society. Happy Mother's Day!

Jane Hampton Cook’s books are on Amazon.com and are great gifts, even at the last minute, for Mother’s Day.

Awesome Mother’s Day piece putting this celebration in historical perspective. Thanks Jane!