Pt. 3: How the Declaration of Independence Birthed Our Greatest Civil Rights Movements

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Susan B. Anthony, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mother Cabrini and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Attacks on Independence Day this year came from many sources. As previously mentioned in part 1 of this series, a freedom of information request revealed that the Air Force Academy is teaching cadets that creation clause of the Declaration of Independence is a myth. As this series has demonstrated, the opposite is true.

The Declaration of Independence’s creation clause that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by a Creator with unalienable rights” inspired America’s greatest civil rights movements that abolished slavery and opened voting rights to all U.S. citizens.

Another Independence Day attack, as Fox News reported, came from a member of Congress, Cori Bush (D-Missouri).

“The Declaration of Independence was written by enslavers and didn’t recognize Black people as human. Today is a great day to demand Reparations Now [sic],” Congresswoman Bush tweeted.

In fact, the Declaration of Independence was formed by a committee that included one slave owner, Thomas Jefferson who wrote the draft, and two non-slave owners who opposed slavery, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, and edited Jefferson’s words.

In contrast to Congresswoman Bush’s assertion, John Adams and his wife Abigail clearly viewed black people as human. In a 1776 letter to John, Abigail criticized those who deprived black Americans of their liberty. Despite the widespread practice of slavery, Abigail interpreted the application of liberty in its purest, most spiritual form.

As previously noted in this series, Abigail famously declared: “The spirit that prevails among men of all degrees, all ages and sexes is the spirit of liberty. For this they are determined to risk all their property and their lives ‘nor shrink unnerved before a tyrant’s face but meet this luring insolence with scorn . . .Tis Thought we must now bid a final adieu to Britain.”

A contemporary of Abigail and John Adams, Samuel Denny of Maine, shared their view that black Americans were human. His religious belief that all men were created in God’s image led him to admonish his brother, a slave owner, that the five-year-old slave in his possession who was to be freed at the age of 30 “has a precious soul as well as we.”

This belief guided abolitionists who called on their fellow Americans to abolish slavery starting in the 1780s when abolitionist societies formed.

One of the most famous abolitionists was novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin revealed the horrors of slavery. The book’s popularity turned many Americans against slavery in the 1850s. When Stowe traveled to Washington D.C. to call upon President Abraham Lincoln to discuss emancipating slaves, Lincoln purportedly said to her:

“So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!”

Indeed, she was. In addition to writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe wrote the foreword for an 1855 book called The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Her purpose was two-fold: to encourage black Americans to be proud of their ancestors’ contributions to the American Revolution and to convince white Americans to oppose slavery and end discrimination.

“In considering the services of the Colored Patriots of the Revolution, we are to reflect upon them as far more magnanimous, because rendered to a nation which did not acknowledge them as citizens and equals, and in whose interests and prosperity they had less at stake. It was not for their own land they fought, not even for a land which had adopted them, but for a land which had enslaved them, and whose laws, even in freedom, oftener oppressed than protected. Bravery, under such circumstances, has a peculiar beauty and merit,” Stowe wrote.

She wanted the contributions detailed in the book to give black Americans “new self-respect and confidence.” Opposing the widespread injustice of slavery, she wanted “their white brothers” to remember that “generosity, disinterested courage and bravery, are of no particular race and complexion, and that the image of the Heavenly Father may be reflected alike by all.”

Abolitionists and suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cade Stanton also tapped the Declaration’s powerful rhetorical logic and emotional appeal.

“‘Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.’ This is the fundamental principle of democracy,” Anthony proclaimed, borrowing a phrase from the Declaration.

Like Stowe, Stanton and Anthony believed it was time to put the Declaration into practice for all Americans, which they conveyed in a speech to the Equal Rights Association after the Civil War.

“We believe that humanity is one in all those intellectual, moral and spiritual attributes out of which grow human responsibilities. The Scripture declaration is, ‘So God created man in his own image, male and female created he them,’ and all divine legislation throughout the realm of nature recognizes the perfect equality of the two conditions; for male and female are but different conditions. Neither color nor sex is ever discharged from obedience to law, natural or moral, written or unwritten. The commandments thou shalt not steal, or kill, or commit adultery, recognize no sex; and hence we believe that all human legislation which is at variance with the divine code, is essentially unrighteous and unjust,” Stanton and Anthony wrote.

They continued to combine their abolitionist and suffragist views and advocated that black men needed the right to vote as well as black and white women.

Women and colored men are loyal, liberty-loving citizens, and we cannot believe that sex or complexion should be any ground for civil or political degradation. Against such outrage on the very name of a republic we do and ever must protest; and is not our protest against this tyranny of ‘taxation without representation’ as just as that thundered from Bunker Hill, when our Revolutionary fathers fired the shot which shook the world? ... We respectfully and earnestly pray that, in restoring the foundations of our nationality, all discriminations on account of sex or race may be removed; and that our government may be republican in fact as well as form; A GOVERNMENT BY THE PEOPLE, AND THE WHOLE PEOPLE; FOR THE PEOPLE, AND THE WHOLE PEOPLE.

The abolition movement came to fruition through the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 19th Amendments to the Constitution. These amendments abolished slavery, declared freed slaves to be U.S. citizens, protected voting rights for black men and eventually voting rights for all women.

The first American to be canonized by the Catholic church, Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini, was an Italian immigrant to America in the late 1800s. At the time she started her “empires of hope” through numerous charitable organizations, Catholics and Italian immigrants were experiencing discrimination. She became an activist on their behalf.

“We are bold or we die. That is how I learned to live in America,” she said.

An upcoming movie about her, CABRINI by Angel Studios (the same distributor for the current hit film, Sound of Freedom, also includes her belief in the Declaration of Independence’s creation clause. The movie includes these lines. “I am a woman, and I am Italian and we are all human beings. We are all the same.”

The Declaration of Independence also inspired Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a former slave, journalist, suffragist, and anti-lynching activist.

“The flower of the 19th century civilization for the American people was the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of all manhood. Here at last was squaring of practice with precept, with true democracy, with the Declaration of Independence and with the Golden Rule,” Wells-Barnett wrote.

The Declaration’s aspirational core philosophy influenced the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s because it was not fully realized for black Americans.

“But 100 years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination,” Martin Luther King, Jr. declared in his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. King looked to the Declaration of Independence as he spoke to thousands on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” King proclaimed. “This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

While concluding that America had defaulted on that promissory note for black Americans through Jim Crow laws, King didn’t believe that America was morally bankrupt. He still had faith in its founding promise. Because of King and civil rights advocates, Congress passed the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s and tore down systemic racist laws.

The spirit of liberty has been a muse for civil rights activists starting with the nation's founding through decades of conflict that led to the ratification of laws purifying and putting into practice the creation clause of the Declaration of independence. The union was not and is not perfect, but it has been made more perfect by those who have embraced the natural rights of all Americans and have put them into practice.

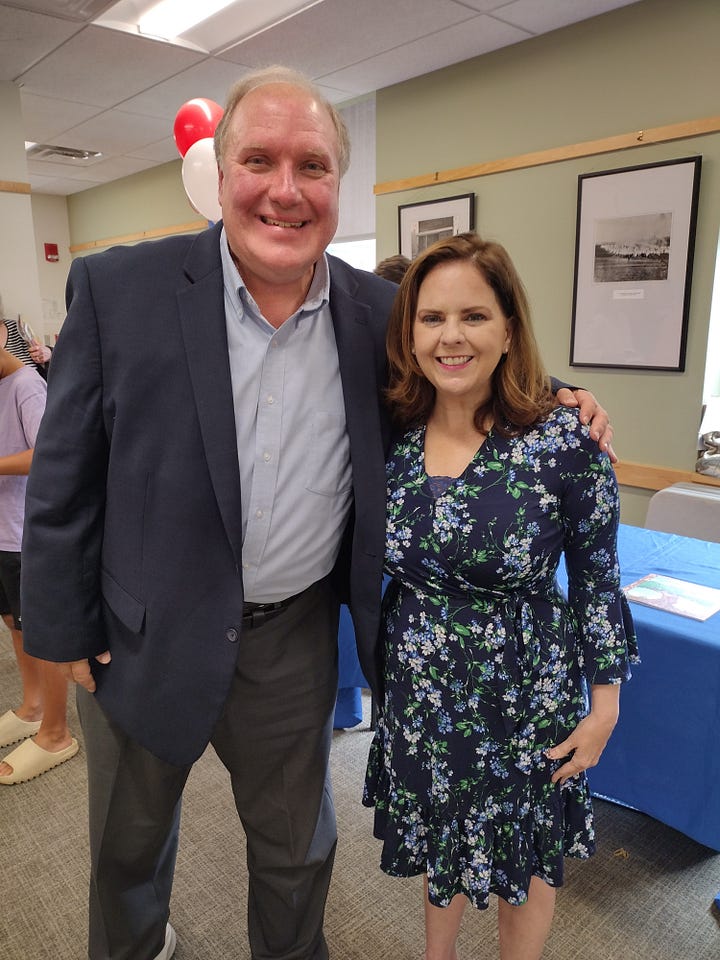

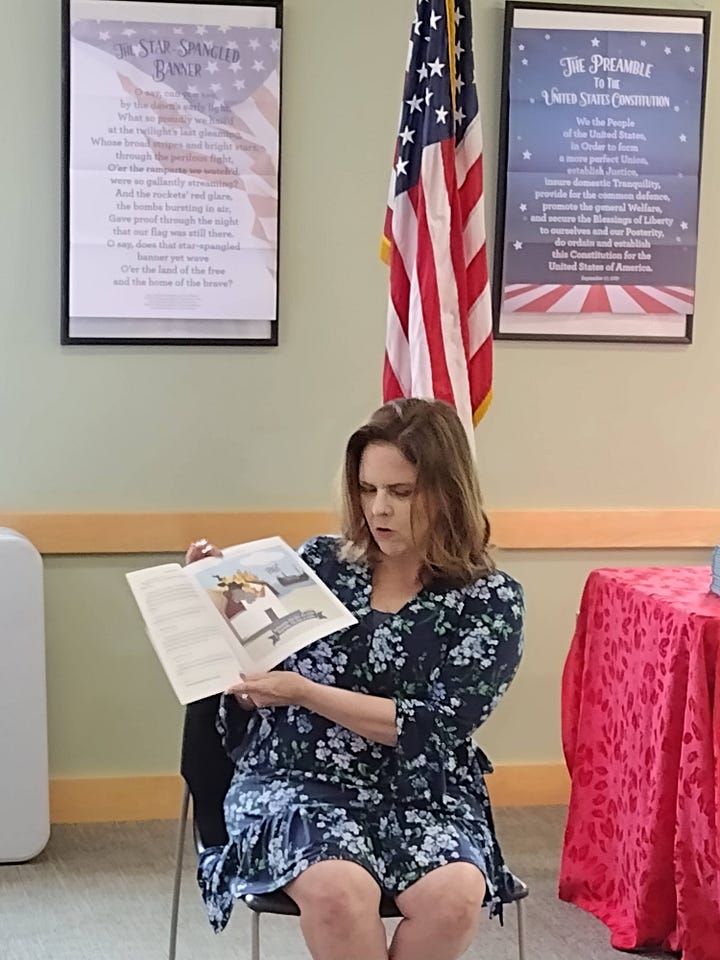

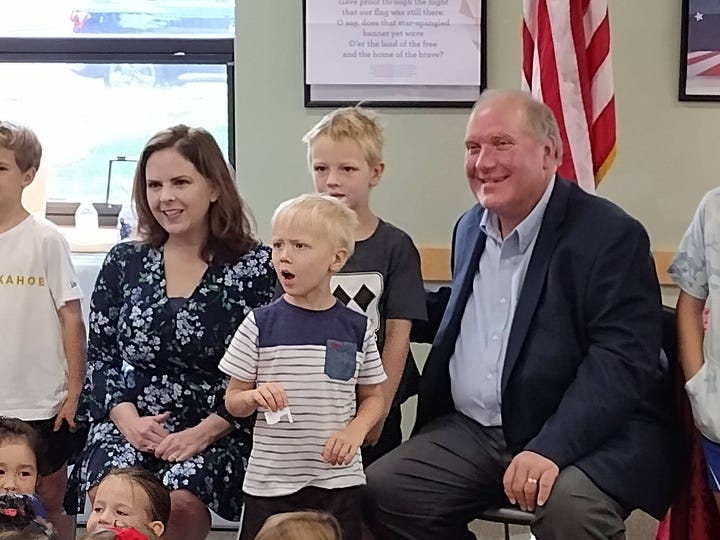

(See you at the Library event, Aug. 5, 2023. Jane read First Fireworks for Independence.