Pt. 3 of 3: How the "9/11" & Great Awakening of the War of 1812 Led to Our National Anthem

Adapted from Jane Hampton Cook's gift book America's Star-Spangled Story

Adapted from Jane Hampton Cook’s gift book America’s Star-Spangled Story.

O Say Can You See?

What comes to your mind when you think or sing our national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner? Can you see what the song’s lyricist, Francis Scott Key, saw? Or do you picture something else on the mural of your patriotic mind? What battlefields from American history tug at your heart? Do you have loved ones who fought for freedom? Which blessings shine brightly from freedom’s timeline?

What did the pilgrims see when their buckled boots clicked and clacked on Plymouth’s rocky shores in1620? Using a spyglass of hope, they saw a land of fertile seed in a place to worship as they please. Inspired by the language of the native tribe of the Great Hills, Massachusetts became the name of a colony chartered for the English crown.

Others who settled farther south also saw future cities on hills. They named sapphire rivers and emerald forests after kings and queens of yore, such as Maryland, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia, after the Virgin Queen Elizabeth I. Ultimately the settlers gave birth to 13 new distinct places.

By the Dawn’s Early Light

What do you do at dawn each day? Snooze? Shower? Shave? Maybe a better question is this: when does your dawn begin each day? Before sunrise? After? Does it come with the help of an alarm clock? A makeup mirror? A coffee pot? A car?

We each have one, a daily awakening, whether it comes as a sudden jolt or slow roll. Sometimes, however, a seemingly ordinary day, becomes an awakening to life. Many turning points in U.S. history started this way.

On April 19, 1775, under moonlight more than seventy men grabbed their muskets and within minutes, gathered in Lexington, Massachusetts. The first shots of the American Revolution were fired there around sunrise, when uniformed British soldiers arrived to steal the colonists stores of ammunition and their weapons to defend themselves.

Another turning point and awakening came on August 24, 1814, after the British military burned the U.S. Capitol, White House, and all of the public government buildings except the patent office. The fear of being conquered was very real as Americans anticipated the next move of the British military.

Francis Scott Key was among those devastated by the loss of his nation’s capital city. But he also had an awakening on September 1, 1814. It started by reading his hometown newspaper at his house in Georgetown, which was located just outside of Washington, DC.

Because local residents feared that British forces would return to Washington City and also try to conquer other cities, the editors of the Federal Republican - Georgetown newspaper issued a call to action on September 1:

“Unless the country is to be abandoned by the people . . . every man should awake, arouse, and prepare for action.”

To these editors, who’d initially opposed the War of 1812, the burning of the Capitol and White House had left them in shock. Now supporters of defending Georgetown and Baltimore, the editors knew it was time to push the people’s recent panic into patriotic productivity. Their eye was on Baltimore, where men were building defenses and preparing for a battle against British soldiers and marines.

Francis Scott Key’s awakening on September 1 deepened when he heard a knocking on his door. Standing there was a familiar face with an unfamiliar story. One of his brothers-in-law, Richard West, had rushed from Marlboro, Maryland, where the British had camped recently. West explained that their friend, a physician named Dr. William Beanes, had been taken prisoner, by Robert Ross, the British general who had burned Washington, DC, just a few days earlier.

Unjust this news was to Key’s ears. A physician devoted to help those in need, Beanes had opened his home to the British, treated their wounded, and tended their sick. One of the British soldiers had stayed behind and threatened local residents. Beanes had merely made a citizen’s arrest of this enemy combatant who was endangering the lives of others. When General Ross heard what happened, he ordered British soldiers to return to Marlboro and seize Dr. Beanes, the good Samaritan, and imprison him on a British ship.

After telling Key the story of Dr. Beanes’s capture, West asked him a question. Would he intervene and advocate for Dr. Beanes?

Advocating was what this attorney did best. Over the years, Francis Scott Key had helped his clients to sell their estates by advertising them in newspapers, holding public auctions, and certifying the sales. Business had been quite slow of late. War will do that. So stale had his work become, that he’d recently written his mother about changing professions.

“I really think I shall try to purchase a small flock of sheep in the spring, and if the war last on, I shall be obliged to leave Georgetown . . . and turn shepherd,” he explained.

Yet, at dawn each day this father of eleven children preferred to don the hat of an attorney, not the staff of a herder.

“I have not determined upon anything but to stay here and mind my business as long as I can.”

Now he could no longer mind his business. The newspaper’s call to action combined with West’s visit led Key to make a decision. He would leave the comfort and responsibilities of his home to advocate for Dr. Beanes. This mission would first require him to risk rejection from a man whose politics he’d long opposed. Key had been awakened to a new dawn’s early light.

Francis Scott Key had opposed the “abominable war” of 1812, as he’d called it in a letter.

Key was not a supporter of President Madison. In fact, he had been one of the president’s most vocal opponents. Despite this, he had worked with the president’s wife, Dolley, to draft the legal papers to free a female slave, Millie, who was married to a free person, Joe, employed by Dolley so Millie and Joe could live together. Key's admiration for Dolley combined with being awakened about the arrest of Dr. Beanes and feeling devastated at the charred remains of the U.S. Capitol and the White House led Key to put aside his political differences with the president.

On September 1, he called upon President James Madison, who was staying at his sister-in-law’s home in Washington City. Granting him a flag of truce and asking the military’s negotiator to accompany him, Madison authorized Key to find the British fleet near Baltimore so he could negotiate for Dr. Beanes’s release.

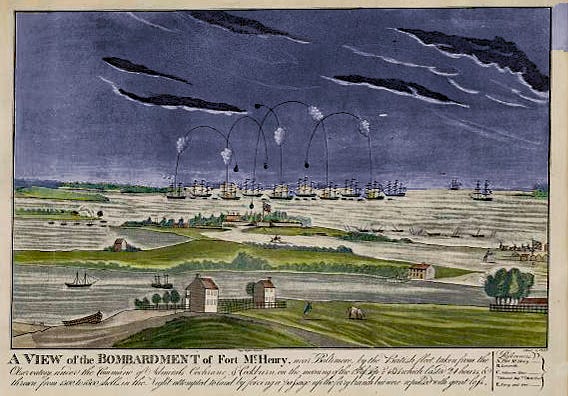

Little did either one of them know where this adventure would take Key. Within days, a British admiral accepted his flag of truce and agreed to free Beanes but forced Key, Beanes, and the American military negotiator to watch the British military attack Baltimore’s Fort McHenry from the point of view of a ship within the British fleet.

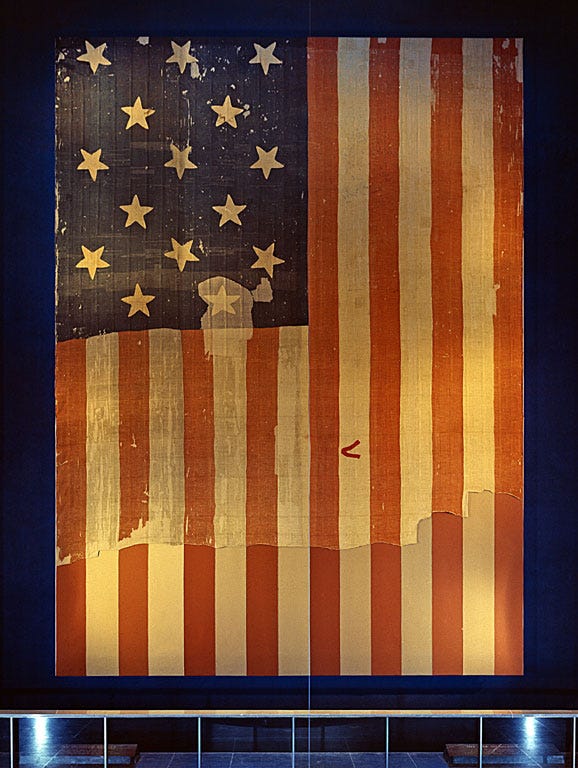

Bombs Bursting in Air

For more than 24 hours, after seeing bombs burst in air and British Rockets leave red glares, Francis Scott Key was relieved to hear the sound of silence. Then through the eerie quiet would he see a white flag of surrender? No, instead he witnessed the giant 42 by 30 foot U.S flag as it flew atop of Fort McHenry. This fifteen-star flag was Fort McHenry’s garrison flag, which was intended to be flown on special occasions. Its presence signaled that the battle was over. The losing British soon fled. Freed from captivity along with Dr. Beanes and the American military negotiator, Key felt his heart bursting with relief and joy on his journey home.

Key immediately poured his emotions out through his pen and wrote the lyrics to The Star-Spangled Banner, which was published in the Georgetown newspaper. Soon, Key’s verses were published throughout the states in newspapers, with instructions to sing it to the tune of To Anacreon in Heaven, a well-known melody.

The burning of the White House and U.S. Capitol by the British military had become the “9/11” of the War of 1812. This devastation along with the news of Dr. Beanes’s arrest had awakened Key to take action, which put him in a position to watch the bombardment and survival of Fort McHenry and inspired him to write the most famous poem of his era. Key’s actions and song embodied the words of a Pennsylvania Congressman.

“The immediate and enthusiastic effect of the fall of Washington was electric revival of national spirit and universal energy,” Congressman Charles Ingersoll reflected.

Though Key knew that The Star-Spangled Banner became popular during his lifetime, he never knew that Congress adopted it as the official national anthem of the United States of America in 1931.

To discover more about this story, check out Jane Hampton Cook’s America’s Star-Spangled Story, an illustrated gift book and a quick and easy read. The book is especially fitting for a family or a classroom.