Night before Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving was an annual tradition in Massachusetts, as John Adams noted in his diary in 1760.

“Night before Thanksgiving.—I have read a multitude of law books—mastered but few,”[i] John Adams, who’d graduated from Harvard College, had written in his diary on Nov. 26, 1760. Adams had a direct connection to New England’s harvest tradition of Thanksgiving. He was a descendent of two Mayflower pilgrims, John and Priscilla Alden, who participated in the historic Thanksgiving in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1621, which gave birth to America’s tradition.

Of the 102 Mayflower passengers who arrived in Dec. 1620, nearly half died in the winter of 1621. At its worst point, the rate of death was two to three a day.

In April 1621, after suspicious surveillance of each other, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag entered into a peace treaty that prevented war and promised mutual defense. The Wampanoag had also suffered severe losses, as high as 75% of their people during a plague that had ended two years prior. Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to plant crops, which enabled them to survive.

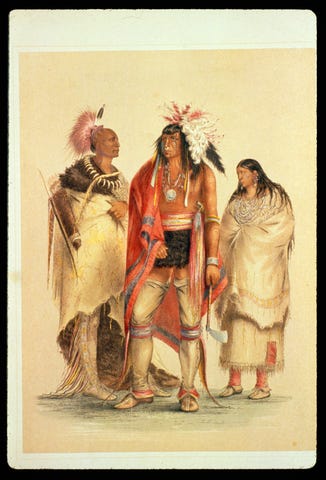

With 90 their Native allies, the Wampanoag of Pokanoket, 53 pilgrims celebrated a three-day harvest Thanksgiving festival in the fall of 1621. Priscilla Mullins, John Adams’s great-great grandmother, was one of only five Pilgrim women who had survived and his great-great grandfather was one of the 24 survivors. The remaining 24 survivors were children.

Edward Winslow’s THANKSGIVING Letter

The best available documentation of this historic Thanksgiving comes from a 1621 letter that Edward Winslow, a Plymouth pilgrim, wrote to a friend in England, which was published in England in 1622 and rediscovered in 1840s.

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, among other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed upon our governor, and upon the captain, and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”[ii]

The Shared Value of Giving Thanks

Giving thanks was a shared value between the Mayflower pilgrims and the Wampanoag, whose alliance of mutual defense lasted over fifty years. Indigenous tribes held celebrations to the Creator while the Pilgrims held days of thanks to Christ the Lord. Days of fasting and giving thanks were part of the Pilgrim’s Christian beliefs.

Giving thanks had been an integral spiritual tradition among native tribes and indigenous people for centuries. Under the music of flutes and drums, the Wampanoag held thirteen ceremonies a year, known as the Thirteen Moons, to give thanks for different food-gathering purposes. During the multi-day Green Corn Ceremony, they did not eat the corn until they had given a proper thanks to the Great Spirit. Climate affected these acts of thanks. Indigenous desert tribes gave ceremonial thanks for the blessing of rain.

Their theologies were different, but they shared a common tradition of humility toward their Creator.

May you have a blessed Thanksgiving in 2022!

[i] John Adams, Diary, Nov. 26, 1760, Founders Online, accessed Feb. 4, 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-01-02-0005-0007-0014.

[ii] Edward Winslow, Thanksgiving, Plimoth Patuxet Museums, , accessed Feb. 8, 2022, https://www.plimoth.org/learn/just-kids/homework-help/thanksgiving/thanksgiving-history.