The Trump Trial--Has America Crossed the Rubicon?

An excerpt about a sham trial from American Phoenix

Did the American legal system and political class cross the Rubicon this week by prosecuting and convicting a former president of the United States? Alas. So, it seems. This unprecedented move against Donald Trump, the 45th President of the United States and Republican presidential candidate for the 2024 presidential election, has shaken America at its core. Emotions are understandably high.

American leaders are not supposed to use the judicial system to work out political and policy differences. That’s what elections are for. During an election season, that job is for the people, not the courts. That’s why this is such a big deal. This is historic.

America may never be the same, just as Rome was never the same after Julius Caesar crossed the real Rubicon, an Italian River, with his army in 49 BC. His unprecedented move against the Roman Senate launched a civil war. The event was so seismic that the phrase “crossing the Rubicon” now means taking an irrevocable step.

Famed attorney Alan Dershowitz, a lifelong Democrat, compared New York District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s prosecution of former President Trump to Joseph Stalin, the longest-serving communist leader of the Soviet Union and his secret police chief, Lavrentiy Beria.

“(Bragg’s) actions in bringing a criminal charge here are akin to the actions of Stalin and Beria and will create a precedent for all American prosecutions in the future,” Dershowitz told attorney and journalist Megyn Kelly.

Dershowitz declared that if you want to get the mainstream media to praise you in the future then “just prosecute your political opponents, make up crimes, get the right jury, get the right venue, get the right judge and you will have your political career enhanced.”

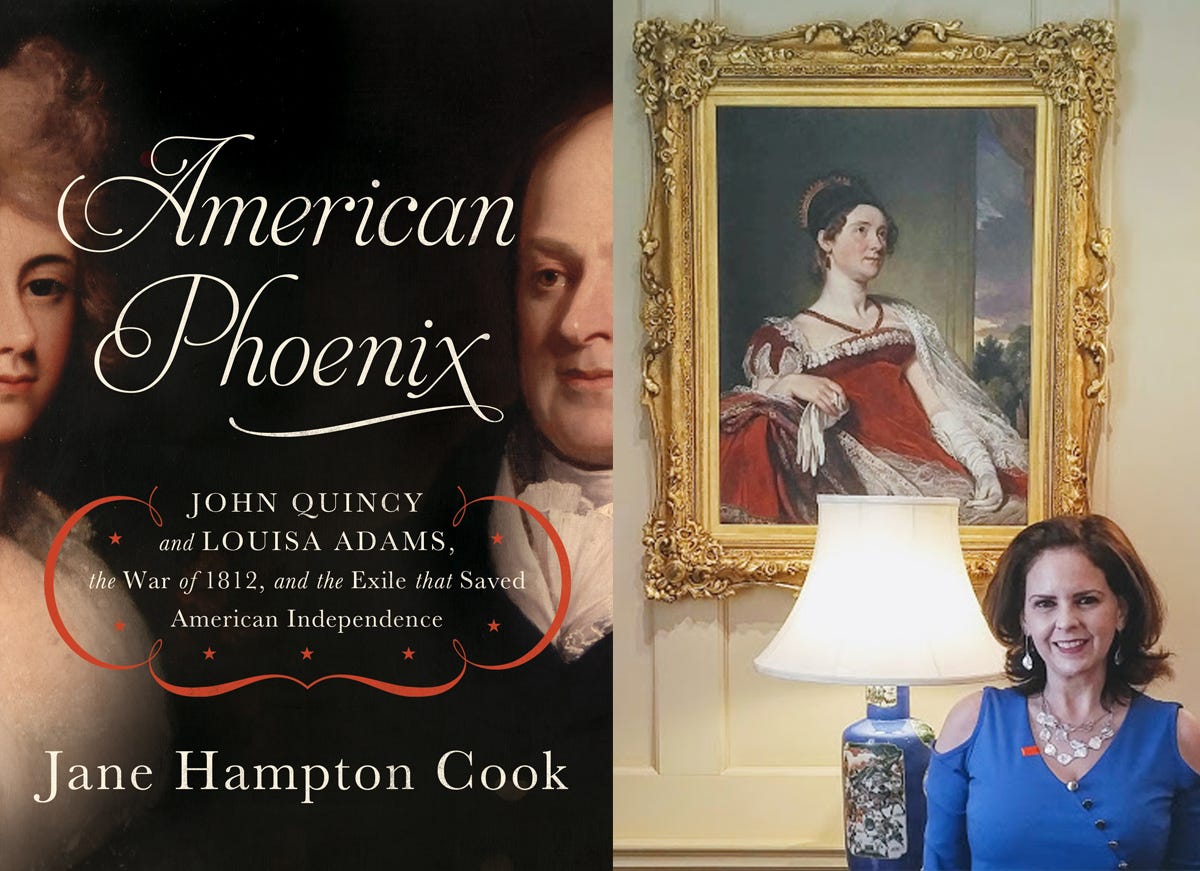

In the wake of President Trump’s trial and conviction, my mind has drifted several times back to a true story I wrote in my book, American Phoenix, about a sham trial that Napoleon orchestrated behind the scenes to rid himself of a rival. I’ll let you make comparisons to today in your own mind but thought I’d share this story as an example of what can happen when judicial norms are abandoned.

For some background, in 1810, John Quincy Adams served as America’s top diplomat to Russia. He and his wife Louisa lived in St. Petersburg, Russia, where they mingled with other diplomats. Adams called his appointment an “honorable exile.” He did not enjoy the rank of ambassador.

Only officially recognized by four nations at the time, America’s status on the world stage was small and weak. As a result, Adams was called a minister, a lower-ranking position than an ambassador. Under these difficult conditions, Adams was doing his best to curry favor with Russia’s Emperor, Alexander I. This was royal Russia, not the Soviet Union known for communism a century later.

Adams had discovered that his nemesis wasn’t the Russian emperor. Rather, in the era of Napoleon, the French Ambassador to Russia, Ambassador Caulaincourt, was proving to be Adams’s greatest adversary. In September 1810 Adams learned that Caulaincourt had played a role in the apprehension of a nobleman that Napoleon had put on trial in a sham trial.

From American Phoenix:

On the morning of September 12, 1810, John Quincy Adams shared a conversation with his friend, Mr. Montréal. The pair had often exchanged books and discussed current events. On this day Montréal decided to tell Adams the truth behind French Ambassador Caulaincourt.

Six years earlier as an aide-de-camp general to Napoleon Bonaparte, Caulaincourt led a corps of French troops. In March 1804, he received an order to go to Strasbourg, a French border town with Prussia. There on the square, Strasbourg’s mayor handed him a sealed envelope, which contained the most shocking requirement of Caulaincourt’s military career.

Napoleon ordered him to use his troops to capture and imprison the Duke d’Enghien, a member of the Bourbons, the family behind the French monarchy that the French people had overthrown years earlier during the French Revolution.

The mission was odd because the duke’s whereabouts were not a secret. With the full consent of Napoleon, the Duke d’Enghien had lived in exile in Prussia. His banishment from France was strange because it was open. He wasn’t hiding from Napoleon.

On several occasions Napoleon had allowed the duke to cross the border to attend plays in Strasbourg. What no one knew was just how paranoid the French emperor had become. He was showing tyrannical stripes. Napoleon feared that the duke was conspiring to create a new coalition against his government.

Always a faithful soldier, Caulaincourt obeyed Napoleon’s orders. He and his French dragoons secretly crossed the Rhine River and surrounded the duke’s house.

“The duke had notice of the approach of French troops, and was advised to make his escape, as it was supposed they had no other object but to take him; but . . . refused on the idea that there could be any design to seize him,” Adams recorded.

Caulaincourt’s troops captured the duke and took him to prison that night. In an overnight tribunal in Strasbourg, a military commission prosecuted the duke for taking up arms against France in the French Revolution and plotting to overturn the current French government. The duke was shot a week after his capture.

In the days that followed, newspapers published witnesses’ statements presented at the tribunal. Many of these witnesses cried foul. They claimed that their statements were fabrications. The trial was a sham. The duke’s unjust death reminded many in France of the French Revolution, when members of the nobility were mercilessly executed after bogus accusations.

Although the French people had once held high hopes for Napoleon, he now seemed no better than the murderous generation before him. In denying the duke a fair trial and quickly executing him, Napoleon had become a tyrant. He'd crossed the Rubicon.

“[Caulaincourt] was very much distressed having such a commission entrusted to him but he executed it,” Adams noted.

Emperor Napoleon had rewarded Caulaincourt by giving him the ambassadorship to Russia along with other honors and titles. When the Russian nobility learned that Caulaincourt was an accomplice in the duke’s death, they were outraged. Caulaincourt’s appointment became so controversial that he was forced to defend his role in the incident to Emperor Alexander. Accepting Caulaincourt’s explanation, Alexander vindicated Caulaincourt.

The Russian czar concluded that the French ambassador had been unaware of the sham and had merely followed his commanding officer’s orders. Alexander issued an exoneration letter to the Russian elite. They put the matter aside. By this time in 1810, Ambassador Caulaincourt’s high style and lavish parties had made him a favorite among these same nobles in St. Petersburg.

Disturbed by the story of the duke’s death and suspicious of Caulaincourt, Adams was more determined than ever to stand up for his country and against Napoleon.